Did you hear that Pope Francis endorsed Donald Trump for president?

Or that Hillary Clinton sold weapons to ISIS?

Crazy, right?

And … 100 percent false.

But if you were one of the millions of people drawn to a bogus headline in your Facebook feed — or other social media platform of choice — and found yourself reading an article on what seemed like a legitimate news site (something like, say, The Political Insider, which “reported” the Clinton-ISIS story), then why wouldn’t you believe it? I mean, people you supposedly trust shared it with you and it ranked high in the Google search. How could it be made-up information?

Welcome to the world of “fake news.”

Digital deception

It comes as little surprise that the web is chock full of commercial click-bait hoaxes: get-rich-quick schemes, free Caribbean cruises, erectile dysfunction treatments … you name it.

But as it turns out, the internet is also teeming with bogus information sites that masquerade as real news. And in the run-up to the 2016 election, many of these hoax news posts spread like wildfire. [Snopes, a fact-checking site, maintains a comprehensive and growing list of fake news outlets.]

President-elect Donald Trump’s contempt for “the mainstream media,” an industry he uniformly dismisses as a corrupt, lying “bunch of phony lowlifes,” has further obscured the boundaries between fact and fiction. So, too, has his use of Twitter to widely disseminate unsubstantiated allegations and, on numerous occasions, downright falsehoods.

Even President Obama weighed in (while still president), assailing the rapid accumulation of fake news as a “dust cloud of nonsense.”

“If we are not serious about facts, if we can’t discriminate between serious arguments and propaganda, than we have problems,” he said at a recent press conference.

Fake news, real profit, serious consequences

In fact, a recent BuzzFeed News analysis of election-related web articles published in the three months before Election Day found that the 20 most popular fake news stories generated significantly more engagement on Facebook (shares, reactions, comments) than did the top 20 real news stories from major news outlets like the Washington Post and New York Times.

And of course, the more engagement, the more ad revenue; a major financial incentive for unethical folks with overactive imaginations to whip up ever more outlandish, attention-grabbing conspiracy theories.

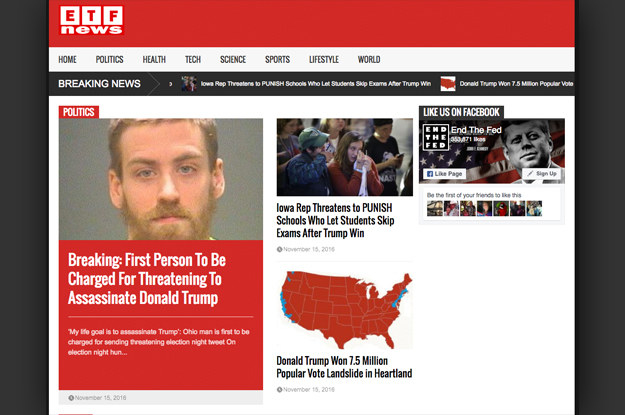

According to the analysis, the majority of the most popular and prolific purveyors of fake news — websites like Ending the Fed and InfoWars — are either full-on hoax sites or “hyperpartisan” right-wing platforms that creatively obscure the truth (a handful of left-wing sites were also in the mix).

Strangely, BuzzFeed also found more than 100 U.S. politics websites run out of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, usually authored by web-savvy, entrepreneurial young people — including teenagers — trying to make a fast buck by creatively duping American media consumers.

One recent notably viral fake news headline espoused an utterly baseless conspiracy theory that a Washington, D.C. family-friendly pizza place was actually a front for a child sex ring run by Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager. Michael Flynn, Jr., son of retired U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn — Trump’s pick for national security adviser, and a Clinton-related conspiracy theorist himself — further promoted the story, while serving on Trump’s transition team, by sharing it with his thousands of Twitter followers. The younger Flynn has since been removed from the transition team due to his aggressive trolling habit.

But the bogus rumor, which became known as Pizzagate, had some serious ramifications when a man armed with an assault rifle entered the restaurant on Sunday, Dec. 4 and fired several shots in what he later told police was an attempt to “self-investigate” the claim (there were no reported injuries).

And no, you really can’t make this stuff up.

To what degree the overall proliferation of fake news affected the election results remains unclear. But it almost certainly did have some impact, particularly on undecided voters.

After initially deflecting criticism that his company bore some level of responsibility for the dramatic spread of political misinformation, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg published a post (on Facebook, of course) less than a week after the election, stating: “We have already launched work enabling our community to flag hoaxes and fake news, and there is more we can do here.”

Several days later, both Google and Facebook announced new efforts to prevent identifiable fake news sites from using their respective advertising networks to generate revenue.

Fake news is nothing new

Fake news has long had a presence in America’s media landscape: Since the colonial period, various news outlets have played fast and loose with the truth for commercial or political gain. A particularly notorious era of journalistic misinformation emerged in the 1890s when competing newspapers owned by rival media titans William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer fought mercilessly for the attention of readers by liberally embellishing stories to sell more papers, a style that became known as yellow journalism.

But the sheer volume of information at our fingertips (and thumbs) today, and the ease with which we can inadvertently spread falsehoods with the simple click of a “share” button, puts us in uncharted territory.

Impressionable young minds

Young people are among the most vulnerable and impressionable consumers of this kind of misinformation, according to a recently released study by Stanford’s History Education Group. Researchers collected nearly 8,000 responses from middle school, high school and college students — aka “digital natives” — around the country who were asked to evaluate online information presented in tweets, comments and articles.

“Overall, young people’s ability to reason about the information on the Internet can be summed up in one word: bleak,” the report states.

“Our ‘digital natives’ may be able to flit between Facebook and Twitter while simultaneously uploading a selfie to Instagram and texting a friend. But when it comes to evaluating information that flows through social media channels, they are easily duped.”

The researchers were consistently “shocked” by the number of students who couldn’t effectively evaluate the credibility of the information they were presented with.

More than 80 percent of middle schoolers in the study believed that “native ads” resembling articles were actually real news stories, even though they were labeled “sponsored content.”

High school students were asked to evaluate a post from a popular image-sharing site featuring a picture of unusually formed daisies and titled “Fukushima Nuclear Flowers: Not much more to say, this is what happens when flowers get nuclear birth defects.” Despite the complete lack of attribution or evidence, most students accepted the picture at face value.

“They didn’t ask where it came from. They didn’t verify it. They simply accepted the picture as fact,” Sam Wineburg, a history and education professor at Stanford University, and the lead author of the study, told NPR in a recent interview.

Many of the high school students in the study also couldn’t tell the difference between real and fake news sources in their Facebook feed.

Meanwhile, most college students in the study didn’t suspect any kind of bias in a tweet from a left-leaning activist group that cited a public opinion survey on gun ownership and background checks.

New polling shows the @NRA is out of touch with gun owners and their own members https://t.co/wm6weuaCbd #NRAfail pic.twitter.com/y4K4r5EcYX

— MoveOn.org (@MoveOn) November 18, 2015

It’s incumbent on educators, the study authors note, to show students how to be more discerning about the information they consume. In other words, how to identify fact from fiction and not to be a sucker.

“But the only way we can deal with these kinds of issues are through educational programs and recognizing that the kinds of things that we worry about, the ability to determine what is reliable and not reliable, that is the new basic skill in our society,” said Wineburg.

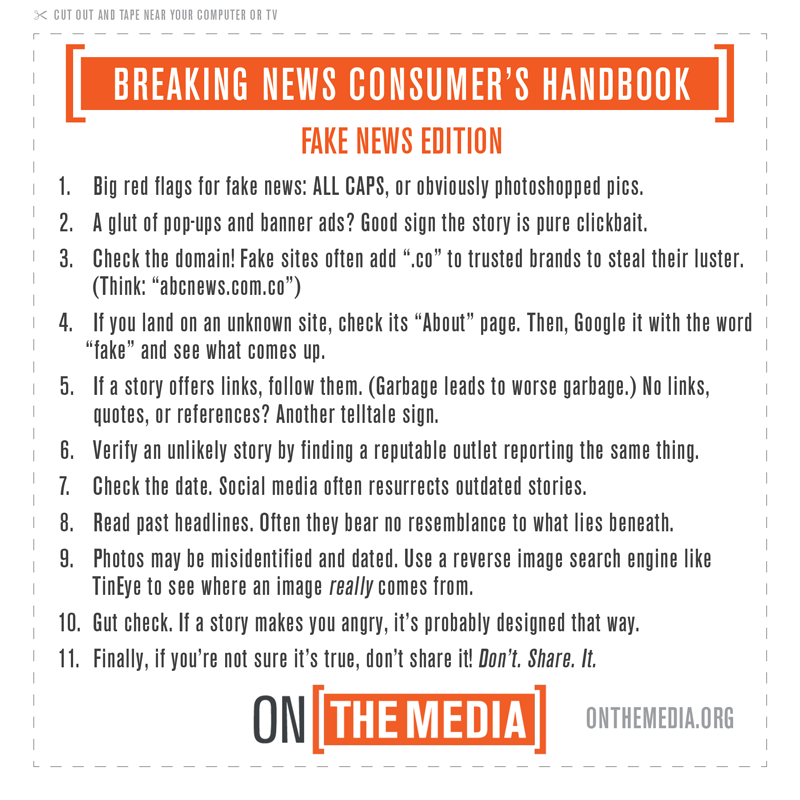

Along those lines, WNYC’s On the Media made this nifty cheat sheet, which combined with an array of excellent, non-partisan political fact-check sites, provide the necessary tools to weed out the fake and focus on what’s really going on.