Should politicians be able to create state voting districts that benefit their own parties?

That’s the key question the Supreme Court will take up during its next term, which begins in October. At stake is the future of gerrymandering, an entrenched electoral tactic practiced in most states wherein the majority party redraws district lines every 10 years to consolidate power.

In several recent cases, the High Court has prohibited state parties from considering the racial makeup of communities when drawing district maps. But it has not ruled against straight-up partisan gerrymandering: when parties draw lines for pure political advantage. The court’s decision could reshape how U.S. elections are conducted.

In separate opinions in May and June, the court struck down two North Carolina congressional districts and 28 state legislative districts, ruling that race played a major role in drawing the lines.

The court also recently invalidated how the Republican-controlled legislatures in Alabama and Virginia drew some of their legislative districts, determining that, as in North Carolina, black voters were intentionally packed into a handful of districts, unconstitutionally weakening the power of their vote. The Texas legislature has faced similar setbacks: A federal court in March determined that Republican lawmakers there drew the state’s congressional map in a way that also intentionally discriminated against minority voters.

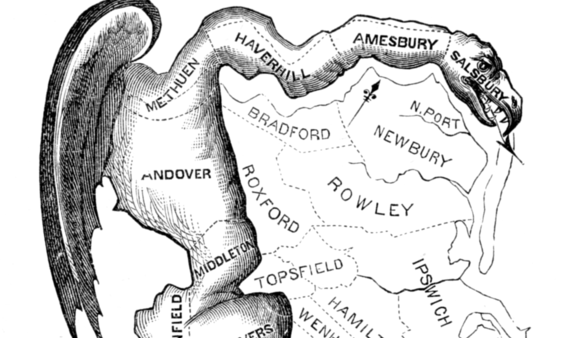

Gerrymandering dates back to Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who in 1812 engineered the drafting of his state’s electoral districts to directly benefit his own party. The strange shapes of the new district maps, it was said, resembled a salamander. Hence … the gerrymander.

It’s par for the course in the opaque ritual known as redistricting. Following the census every 10 years, states redraw their congressional and legislative boundaries so that all districts have roughly equal populations. But as long as they contain the same number of people, those districts can be reconfigured in any number of ways, shapes and forms. If you put your mind to it, you can come up with some seriously creative cartography.

In a whopping 37 states, the party that controls the statehouse also controls the redistricting process, something that sets the U.S. apart from virtually every other democracy in the world.

This, of course, guarantees some degree of seemingly unfair partisan edge. The party in control is likely to redraw district lines in a way that ensures they’ll control the most seats, even if they win fewer overall votes. But here’s the rub: Partisan gerrymandering is generally permitted as long as there’s no evidence that it discriminates against specific populations.

The states under recent legal scrutiny all argued, albeit unsuccessfully, that, while their district maps were drawn to give the majority party a clear electoral advantage, there was no intent to racially discriminate.

This process has huge impact on the balance of power in our political system and plays a large role in determining how much our votes actually count on Election Day.

Take the 2014 midterms. It was a rough one for Democrats. They lost their Senate majority, slipped further into the minority in the House and got clobbered in state elections, where Republicans took 31 out of 50 governorships and secured a record 68 state legislatures.

But as Evan Bonsall and Victor Agbafe write in the Harvard Political Review, a quick voting analysis suggests there was some serious political rigging at play. Looking at total votes cast nationwide in the 2014 U.S. House elections, they found that Democrats actually received 1.4 million more votes than Republicans, even though Republicans won 46 more seats. These disparities were similar in state legislative elections, where Republicans won 948 more statehouse seats despite receiving fewer popular votes overall.

The authors note that Democrats are far from blameless. Election results were often skewed in their favor from the 1960s to the 1990s, and states like Illinois and Maryland are still heavily gerrymandered to protect Democratic majorities.

So prevalent is the process that former President Barack Obama is teaming up with Eric Holder, his old attorney general, to try to change how political districts are formed.

With an eye on 2021, when states next redraw their lines, Holder has stepped up to lead the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, a newly formed political group pushing redistricting reform. He argues that redistricting efforts are often unfair and undemocratic, orchestrated by Republicans to help solidify their power.

“[Obama] thinks, and I think, that this is something that threatens our democracy,” Holder told the New York Times. “We have a system now where the politicians are picking their voters, as opposed to voters making selections about who they want to represent them.”

For more on the strange geometry of redistricting and gerrymandering, check out this great interactive by Newsbound. Note that this resource was originally produced for Change Illinois, a group that advocates for state political reform (hence the Illinois references). It’s since been updated — with editorial input from yours truly — to present a more balanced analysis.

And if you’re still hungry for more, check out this related collection of Lowdown posts from 2012.